La Niña is coming, raising the chances of a dangerous Atlantic hurricane season – an atmospheric scientist explains this climate phenomenon

Published in Science & Technology News

One of the big contributors to the record-breaking global temperatures over the past year – El Niño – is nearly gone, and its opposite, La Niña, is on the way.

Whether that’s a relief or not depends in part on where you live. Above-normal temperatures are still forecast across the U.S. in summer 2024. And if you live along the U.S. Atlantic or Gulf coasts, La Niña can contribute to the worst possible combination of climate conditions for fueling hurricanes.

Pedro DiNezio, an atmosphere and ocean scientist at the University of Colorado who studies El Niño and La Niña, explains why and what’s ahead.

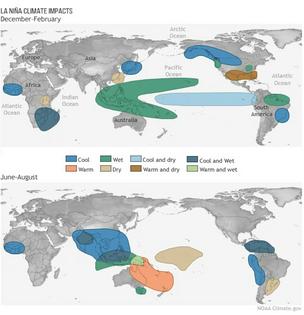

La Niña and El Niño are the two extremes of a recurring climate pattern that can affect weather around the world.

Forecasters know La Niña has arrived when temperatures in the eastern Pacific Ocean along the equator west of South America cool by at least half a degree Celsius (0.9 Fahrenheit) below normal. During El Niño, the same region warms instead.

Those temperature fluctuations might seem small, but they can affect the atmosphere in ways that ripple across the planet.

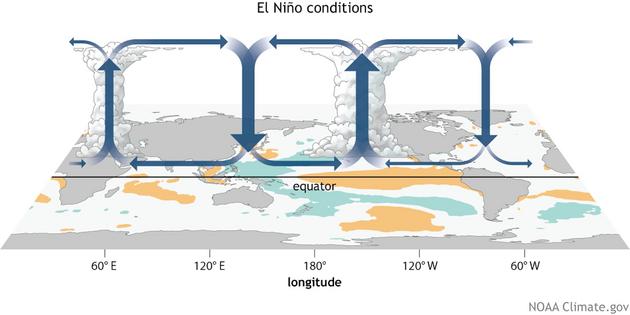

The tropics have an atmospheric circulation pattern called the Walker Circulation, named after Sir Gilbert Walker, an English physicist in the early 20th century. The Walker Circulation is basically giant loops of air rising and descending in different parts of the tropics.

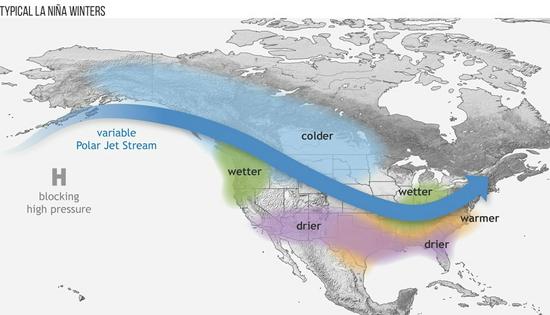

Normally, air rises over the Amazon and Indonesia because moisture from the tropical forests makes the air more buoyant there, and it comes down in East Africa and the eastern Pacific. During La Niña, those loops intensify, generating stormier conditions where they rise and drier conditions where they descend. During El Niño, ocean heat in the eastern Pacific instead shifts those loops, so the eastern Pacific gets stormier.

EL Niño and La Niña also affect the jet stream, a strong current of air that blows from west to east across the U.S. and other mid-latitude regions.

During El Niño, the jet stream tends to push storms toward the subtropics, making these typically dry areas wetter. Conversely, mid-latitude regions that normally would get the storms become drier because storms shift away.

...continued

Comments