When the Supreme Court said it’s important to move quickly in key presidential cases like Trump’s immunity claim

Published in Political News

When former President Donald Trump’s attorneys argue before the U.S. Supreme Court on April 25, 2024, they will claim he is immune from criminal prosecution for official actions taken during his time in the Oval Office. The claim arises from his federal charges of attempting to overturn the 2020 presidential election results, but also may apply to the charges he faces over hoarding classified documents after leaving office.

No Supreme Court has decided this question, nor has any of its rulings said definitively what counts as an official act and what does not. Numerous commentators have called on the justices to decide the case rapidly.

But to the justices, and to me as a scholar of American politics and law, perhaps no commentator is as persuasive as the Supreme Court itself – in particular, in a ruling from 50 years ago.

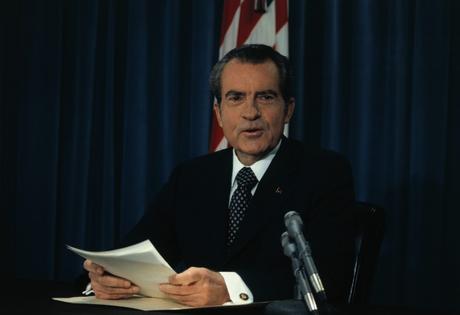

Back then, in a case connected to the deepening Watergate scandal, then-President Richard Nixon claimed that all of a president’s conversations during his term in office were confidential and could not be subpoenaed into evidence by a court, even if they contained information relevant to a criminal prosecution.

In 1974, the Supreme Court accepted, heard and decided Nixon’s claim within two months, with Chief Justice Warren Burger explaining it had done so “because the matters at issue were of urgent public importance.”

So far, the court has acted more slowly in Trump’s case, but may yet heed its own words of urgency from the past.

By 1974, the Watergate scandal had dragged on for almost two years, tearing the country apart. It was sparked by a burglary of Democratic Party headquarters in Washington’s Watergate Complex in May 1972 and mounting evidence that Nixon had orchestrated a cover-up.

In the summer of 1973, the highly publicized Senate hearings on Watergate publicly revealed the existence of tape recordings of Oval Office conversations. Access to the tapes became critical to establishing what Nixon knew about the break-in and when he knew it.

In November 1973, political pressure forced Nixon to release seven tapes to Judge John Sirica, who presided over a federal grand jury investigating Watergate. Leon Jaworski, whom Nixon had appointed special prosecutor, used those tapes to secure indictments of seven of Nixon’s top advisers for their efforts to cover up the burglary. The indictments were made public on March 1, 1974 – but secretly, Nixon was named an unindicted co-conspirator.

Based on evidence from logs of visits to the White House, Jaworski identified 64 additional tapes that likely contained relevant conversations and persuaded Sirica to subpoena them. Nixon’s team appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals. On May 24, 1974, Jaworski filed a request for certiorari before judgment, a rarely used legal mechanism asking the Supreme Court to get involved before the appeals court heard the case.

...continued

Comments